The Boy Who Wanted to Be a Mermaid

I just got home from seeing the new live-action adaptation of The Little Mermaid on opening day (May 26). I invited a family member to join me, but they changed their mind and didn’t want to go, so I had a solo movie date. And I’m so glad I did, because it was absolutely wonderful.

In the weeks leading up to the movie’s release, I geeked out on everything I could find: articles, interviews, clips from trailers, song snippets, pictures of the cast on the blue carpet. I recorded videos of me singing the songs, and I’m still singing them now.

Seeing Jodi Benson (the voice of Ariel in the 1989 original) and Halle Bailey (starring as Ariel in the 2023 remake) together is absolutely magical. Jodi’s cameo in the new movie was perfect—a sort of “Stan Lee” moment.

There was a family sitting behind me in the theatre, and I heard a mom say to her child, “That’s the original Ariel.” The fact that this mermaid story is shared across generations is one of many things that makes it so beautiful to me.

There is so much I could say about the new movie, and I am still soaking it all in. But this is less of a movie review and more about my relationship with this story and the role it has played in my life.

The original animated film was such an important part of my childhood, and it impacted me so strongly that I have remained a fan into my adulthood. In fact, I have become even more of a fan as my appreciation for the film has grown.

I was 5 years old when it was first released. I barely remember seeing it in the theatre, but I vividly remember seeing the movie poster. And, of course, I watched the VHS tape hundreds of times at home.

I remember one time when I was watching it with my family. I had a little tape recorder and I kept shushing the adults because they were talking during my recording.

I had the floating bathtub toy of Ariel from the McDonald’s Happy Meal.

I played the NES game that was very loosely based on the film, which I still play sometimes as a ROM.

I remember having magazines, and possibly some other things, but I didn’t have a huge Little Mermaid collection.

I was a little boy who primarily liked “little girl” stuff, and adults found it complicated. But to me, it made complete sense. I was this fabulous, queer little boy who was misunderstood.

So, of course I wanted to be Ariel. She was beautiful, freethinking, rebellious, intellectually curious, she loved to collect cool things, and she sang about longing to be somewhere else. I related to her in every sense.

I am not alone in this, as many gay men and queer people in general have proclaimed their love for this movie and how it shaped their identity.

That is, of course, by no accident. The visionary behind the original animated film was a gay man named Howard Ashman, and there is no doubt that his life experiences influenced his lyrics and artistry in many ways.

He worked on three major films for Disney: The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin. Of these, The Little Mermaid feels the most personal, and Ashman’s passion for the project is evident. He was emotionally invested in Ariel, and he wanted the audience to feel it. And we do, to this day.

But the queerness of The Little Mermaid does not originate with Howard Ashman. It can be traced back to the source material: the original 1837 story by Hans Christian Andersen.

In a collection of essays titled My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries, literature historian Rictor Norton posits that The Little Mermaid is an allegory of Andersen’s life, and the story was written as an expression of his unrequited love for Edvard Collin.

The Danish author is known to have had deep feelings for men who did not share his sentiments, which he expressed with great passion through written correspondence.

In his letters to Edvard Collin, he wrote: “I languish for you as for a pretty Calabrian wench… my sentiments for you are those of a woman. The femininity of my nature and our friendship must remain a mystery.”

Collin was married to a woman and presumably heterosexual. He would later write in his memoir: “I found myself unable to respond to this love, and this caused the author much suffering.”

I believe that, 150 years later, Howard Ashman understood this significance and related to it in his own way.

This is most evident in the song “Part of Your World,” which was Howard’s baby. It was the first song written for the film; Howard conceived the idea and lyrics before his collaborator, composer Alan Menken, was introduced to the project.

In his Greenwich Village apartment, Ashman debuted the song to the directors and screenwriters of the film. One of these gentlemen, John Musker, later remarked:

“Howard became Ariel before our eyes and ears, singing fervently with unabashed sincerity. Traffic whizzed by below us out on that cold December night as he poured out his heart in song. He looked up to the ceiling of his apartment as he sang, and it became the out-of-reach human world. He made us see it, too, and feel it, this far-off place of wonder that so entranced this little mermaid.”

There is a video of Howard Ashman in the recording booth with Jodi Benson, coaching her on the dynamics of emotional intensity in her vocal delivery. He knew exactly what he wanted, and Jodi delivered. She sang it from her heart, channeling Howard’s energy, as well as the spirit of Hans Christian Andersen.

As a young boy, I felt that I was right there in the grotto, sharing this personal moment with her. Jodi, as Ariel, was singing it for me—for all of us. She captured all the heartfelt emotion, the isolation and longing, with such deep sincerity. Every syllable of every word was intentional.

Coming from a theatre background, Howard knew how crucial it was to have an “I Want” song, where the leading lady has her own musical number to sing about what she wants out of life, and wins the hearts of the audience.

The song meant so much to him that he fought for it. A Disney executive wanted to cut it from the film because he thought children would find it boring. Howard’s response was: “Over my dead body.”

He was right, of course, and the song has become the defining number of the film. “Under the Sea” is the most famous song because it won all the awards, but “Part of Your World” is Ariel’s song, and epitomizes the spirit of the character and her story.

Halle Bailey’s version in the new film is just as beautiful and intense as Jodi’s version, but it’s important to remember that it was never meant to be a note-by-note reproduction. Halle sang it from her own heart and in her own voice, which is the whole point of the song. She embodied the spirit of Ariel and everything she represents.

When I first heard the new version, I listened to it several times because it was so beautiful and brought me to tears.

Ever since it was first announced that Halle was cast as Ariel in the film, the racists have expressed loud and clear how concerned they are that the mermaid isn’t white, or her hair isn’t red enough, or some other white privilege bullshit. They disapproved of the way she sang the songs, they bashed the clothing she wore, and continued to criticize her casting from day one.

And years later, they still haven’t shut up about it.

I saw this one person online who had the audacity to say: “Halle has such a beautiful voice, but I wish Disney cast her in a different mermaid movie instead and made her her own character. It’s not racist, people just don’t want the original messed with.” Or something to that effect.

Honey, sit down.

First of all, Halle didn’t audition for a different mermaid movie, she auditioned for The Little Mermaid. She was one of many actors who auditioned for the part. She didn’t get the part because Disney “went woke” and purposely cast a black mermaid, and other stupid shit these people say.

She got the part because she gave the best audition. She set the bar and no one could surpass it. Miss Halle Bailey understood the assignment and delivered.

Second of all, these fools protest that their “childhood is ruined” and they “don’t want the original messed with,” and other such nonsense. Their childhood was thirty years ago, around the same time as mine, and my childhood isn’t ruined. My inner child is absolutely delighted.

Nothing is lost by the existence of a different version of Ariel in an adaptation of the story. The original movie still exists, so they can watch the white mermaid sing any time they want.

Plus, Jodi Benson is still alive and well, and still singing her song three and a half decades later. So they can watch the white lady sing it live too!

Of course, I’m being sassy, but it really pisses me off because these people are complaining about things that are not problems. They claim to be fans, but they completely miss the point of the character.

The Little Mermaid is a queer allegory, so why can’t other marginalized minorities also see themselves as the titular character? Why can’t little black and brown kids identify with Ariel the same way I did when I was a little boy?

She represents anyone who feels alone and doesn’t fit in—an outsider, othered, and ostracized. She represents anyone who feels like they’re not being heard and struggles to find their own voice. She represents those who dream and long to be somewhere where they’re accepted and included, and where they can be free to be themselves and explore of their own volition.

That is what Ariel represents.

If you have a problem with a black mermaid, you’re racist. Plain and simple.

Okay, now that I’ve dealt with that, let’s go deeper into the mysterious fathoms below. Ariel is not the only character in The Little Mermaid with queer significance. I would be remiss if I failed to address the octopus in the room.

Anyone who knows me knows how much I really enjoy the character of Ursula, the Sea Witch. It is worth noting that this was something that developed as I got older. When I was a child, I was all about Ariel. But in my adulthood, I came to appreciate Ursula.

I currently own a huge coffee mug, two t-shirts, a pocket watch, and a Funko POP! figure of Ursula. I probably own more Ursula merchandise as an adult than I did Ariel merchandise as a child.

But what is it that makes Ursula so significant?

The primary factor is her design. The animators of the original film sketched many different designs before they discovered the Ursula we have come to know. Many of these early sketches seem rather generic and unmemorable. Ursula is the type of character that needs to make a BIG impression.

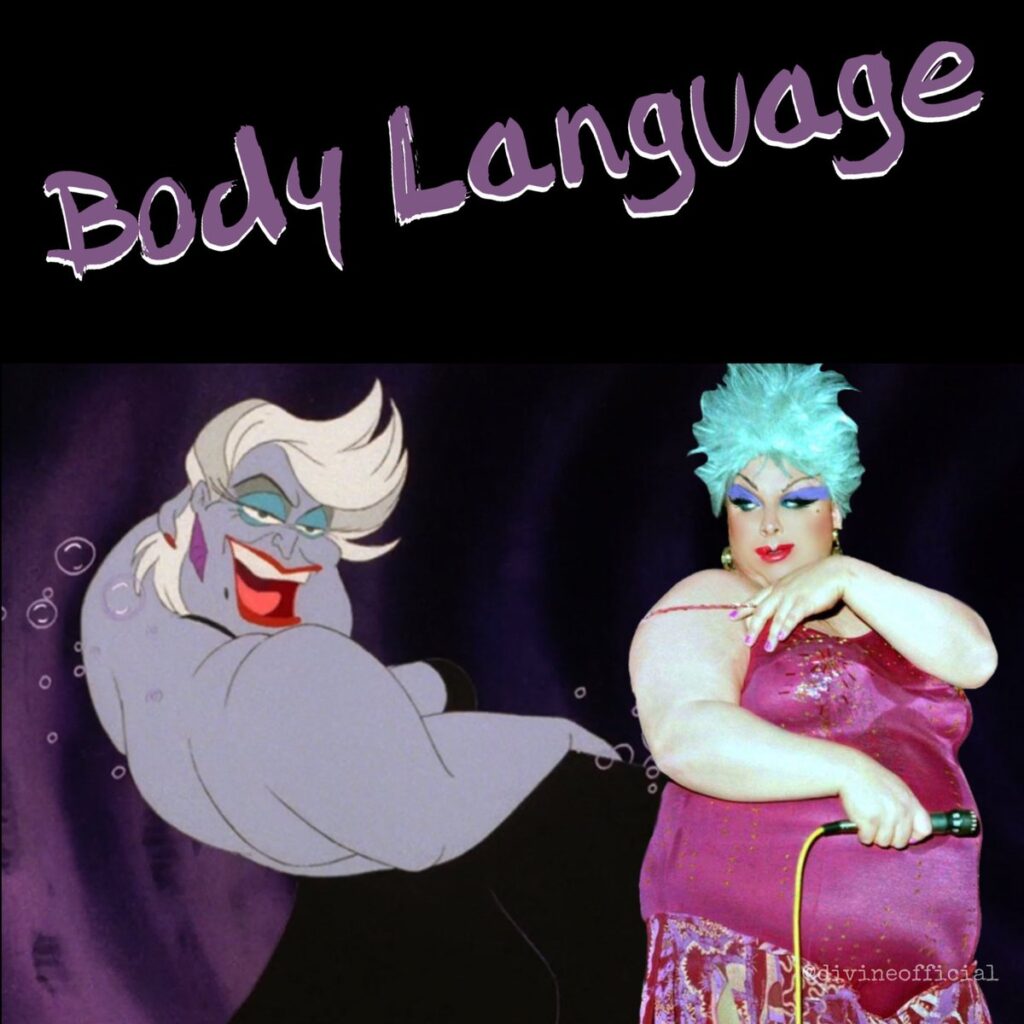

Animator Rob Minkoff (with the encouragement and approval of Howard Ashman) based Ursula’s design on the drag queen, Divine, who starred in John Waters’ films (including the original Hairspray) and had a successful music career.

Harris Glenn Milstead was a sweet and soft-spoken gay man who portrayed the trashy, outrageous Divine character. In many ways, Divine was the perfect template for Ursula: she was loud, brash, imposing, and larger than life.

John Waters once said that Divine didn’t want to be a woman, she wanted to be a monster. Her purpose was to shock and grab her audience’s attention.

Disney never would have allowed it at the time, but I think that Divine would have done a fabulous job voicing Ursula. Unfortunately, she died a year before the release of The Little Mermaid, so she never even got to see the character that she inspired.

I do believe that there was an attempt to not only emulate the look of Divine, but also her voice. The first choice was Bea Arthur of Golden Girls fame, another gay icon. Her husky voice would have made a wonderful Ursula, but she was unavailable.

Pat Carroll won the part of Ursula, and I think she was meant for it. She not only imitated Howard Ashman’s vocal inflections on the song demo (more on that in a moment), she also made the character her own. During interviews, she described her approach to Ursula’s personality as part Shakespearean actor and part used car salesman.

Indeed, Pat Carroll’s Ursula has an air of sophistication and extravagance about her. After all, she once lived in the palace before she was banished, so she probably has expensive taste.

But she is also wicked, menacing, vengeful, and deceitful. So she carries herself with the pomposity of a Shakespearean actor combined with the conniving swagger and charm of a used car salesman.

Ursula’s voice is similar to Pat Carroll’s natural voice, but much deeper. Pat was already known for her distinctive, full-bodied laugh, but when pitched down to Ursula’s register, it became the gravelly cackle that is synonymous with the character. When asked to recreate Ursula during interviews and public appearances, Pat was always delighted to lower her voice and say a few lines.

Just like Ariel’s “Part of Your World,” Ursula’s “Poor Unfortunate Souls” is an iconic song.

When he and Alan Menken recorded the demos, Howard Ashman sang all the songs in character. When he sang “Poor Unfortunate Souls,” he channeled his inner queen and spared no expense in delivering all of Ursula’s villainy and theatricality.

Just like Jodi did with her song, Pat delivered Ursula through Howard’s vision and added her own personality, and also, perhaps inadvertently, channeled a bit of Divine.

The opening chords create a tense dissonance between the 9th and the minor 3rd, which establishes the eerie mood. The melody of the first verse seems to slink around like Ursula’s tentacles, before launching into the bombastic chorus.

And the song would be incomplete without the “Beluga, sevruga” incantation at the end, when she seizes Ariel’s voice. It’s my favorite part of the song.

I have always interpreted the song as a campy cabaret number, with all the flamboyance and grandiose theatricality that one would expect. It is one of my go-to songs when I sing karaoke. I can sing the entire soundtrack, but when I’m channeling Ursula, I’m big, bad, and beautiful.

When the new movie was first announced, there were many talented stars who could have been great candidates for the role of Ursula: Lizzo, Queen Latifah, Tituss Burgess, Ginger Minj, and Rebel Wilson have all performed “Poor Unfortunate Souls” and captured the spirit of the character in their own ways.

So when Melissa McCarthy was cast as Ursula, it gave me some pause. I’m a fan of Melissa McCarthy and I had no doubt that she understood the comedic aspects of the character, but could she sing the song? Would she capture all of Ursula’s wickedness?

Yes, indeed!

From the very first footage of her in the trailers, all doubts were dispelled. She emulated the huskiness of Pat Carroll’s voice, all the way down to the gravelly, witchy cackle, but she also made it her own.

I saw an article in which Jodi Benson said that if Pat was still alive, she would have loved Melissa’s performance. I wholeheartedly agree. I’m sure she would have described Melissa McCarthy as “marvelous!”

Melissa released her inner drag queen for this performance, and girl, did she deliver! She described her character as an old gal who drinks a lot of martinis and smokes a lot of Pall Malls.

She also used adjectives like “juicy” and “dishy,” which I think are synonyms for “perfect” and “fabulous.”

To make this even more delicious, Melissa even has a connection to Divine, as she dressed as the late drag queen for Entertainment Weekly’s Comedy Issue in 2011.

In some ways, Melissa’s Ursula is also more dark and sinister. There are glimpses of mermaid skeletons in her lair, and there is a scene where she holds up several skulls.

At the end of the song, instead of having Ariel sign a scroll, she instructs the mermaid to rip off one of her scales and throw it into the cauldron. A literal blood contract. If that’s not badass, I don’t know what is.

She also got deep into the complicated psychology of Ursula. She portrayed Ursula as a more sympathetic character who is plagued by mental health issues.

This is a pandemic-era Ursula that deals with themes of isolation, feeling outcast, and longing to be somewhere else, but her motives are very different from Ariel.

This brings me to the topic of queer coding.

The Motion Picture Production Code, commonly known as the Hays Code, was a set of strict censorship guidelines in the American film industry from the 1930s to the 1960s.

The list of restrictions was very extensive and based on religious moral values. If you’ve ever watched an old TV show and wondered why the married couple were in two different beds instead of sharing a bed, you can thank the Hays Code.

Queerness and same-sex relationships were called “sex perversion,” and were explicitly forbidden. But that didn’t stop film directors from being sly and dancing around the rules, sometimes literally.

The sissy stereotype was rampant throughout the 1930s. He was flitting, swishy, limp-wristed, weak, cowardly, vain, and melodramatic. He often appeared as a foppish dandy, theatre actor, or a hairdresser.

But these characters were never explicitly stated to be gay or queer. Their sexuality was ambiguous or non-existent. They were implied to be queer through subtext, sometimes for comedic exaggeration, and oftentimes to portray them as undesirable or deviant.

Queer coded characters were portrayed as villains and criminals to contrast with the perfect, white, heteronormative protagonists.

This stereotype became prevalent throughout Hollywood, and Disney was no exception. In fact, Disney has continued to queer code their villains well after the Hays Code was replaced by our modern ratings system.

Prime examples in the Disney canon include: Captain Hook (Peter Pan), Prince John (Robin Hood), Jafar (Aladdin), and Scar (The Lion King).

They are effeminate and dainty with flamboyant affectations. They are also gaunt, gangling, and cowardly, in stark contrast to the strong, courageous, and conventionally attractive protagonists.

Gaston (Beauty and the Beast) is queer coded by overcompensating in his hypermasculine presentation to hide his queerness, which draws even more attention to it.

He opens his shirt and sings the line “every last inch of me’s cover with hair” as he winks at the camera. Come on now. He’s basically a 1970s Castro clone in an 18th century French village.

Whenever the topic of queer coded Disney villains comes up, Ursula is always mentioned, and often she is at the top of the list.

Critics will mention that the character was modeled after Divine, and sometimes they mention Howard Ashman, but they fail to acknowledge that the reference was intended more as tribute and not defamation.

Divine would have LOVED to be portrayed as a villain!

I have no doubt that Gaston was also an inside joke for Howard, a sort of caricature of men he knew who behaved like that.

Howard was playing with tropes and archetypes from his own community as if they were actors in his own plays.

He was not the first to do so. Throughout the history of film, gay people in the industry occasionally slipped in these types of references as a sly wink to those “in the know.”

Perhaps a director or screenwriter, or a wardrobe or set designer, would sneak in something and the general audience would remain oblivious, but perceptive homosexuals would get the hint.

This is no surprise as queer folk have always communicated through our own language and symbols. Throughout most of history (and even sometimes today) we couldn’t be out in the open, so we had to invent secret ways of identifying each other.

Polari, lavender, green carnation, hanky code, yaaas gurl… we’ve always had queer codes of our own.

So while it cannot be denied that the early film industry was responsible for perpetuating harmful, derogatory stereotypes, that is only part of the story. The truth is that the topic of queer coding is not black or white, but many shades of gay.

There are many queer people who love Disney villains. There is an entire fandom who love the villains because they’re gay. They’re fabulous, outrageous, ostentatious, and they usually have a really big, show-stopping musical number. They’re unconventional, strong-willed, and they push back against the establishment.

They also appeal to our emotionality. Villains are often outcasts who live on the fringes of society, rejected by their own families. Odd, misunderstood, don’t fit in.

In many ways, we relate to them.

Sympathetic villains have become a popular trope over the past 20 years. Every villain has a back story, and sometimes it is tragic.

There has been much discussion about characters such as Darth Vader (Star Wars) and Magneto (X-Men). Sometimes the villain’s story is completely reimagined and expanded, such as the musical Wicked, and the films Maleficent and Cruella.

We psychoanalyze these characters and their motives because we see the humanity in them. The case of Magneto is particularly interesting, as he was a victim of the Holocaust, and the root of his anger towards humanity is the oppression and violence he faced.

We are reminded that these characters are just as complicated and nuanced as we are. They carry traumas, injuries, scars, and imperfections that make them relatable.

The classic story of good vs. evil is the narrative we’ve perpetuated for so long, but if we look deeper, there is much more to these characters than what appears on the surface.

And, of course, villains are not the only characters who are queer coded. Remember our friend, Ariel? The Little Mermaid? She was queer coded from the very beginning.

I believe that Ariel and Ursula represent two different aspects of queerness. Ariel’s song is more intimate, personal, and inward, whereas Ursula’s song is big, bold, and completely outward. This is also represented in the contrast of their physical appearance.

There is an alchemical yin-yang dynamic in effect, in which the two seemingly opposing forces are actually two parts of the same thing. When we integrate these parts of ourselves, we discover the complex wholeness of our being.

Perhaps Ariel represents the heart of the story, who we really are beneath the surface, and Ursula represents the armor we put on to face the challenges of being a queer person in this world.

That is just one interpretation. I think, since this story is so personal to many people, we all relate to these characters in our own ways.

So, as you can see, I get deeply philosophical about The Little Mermaid. It has been the only movie and the only story that has remained consistent throughout my life, and its significance has grown and evolved with me.

That’s why I was so excited when the new movie was announced. I have waited 34 years for a proper live action Little Mermaid film. To see Ariel’s world come to life on the big screen was a dream come true.

As I predicted on social media, I was there on opening weekend, I was ecstatic, and I did cry. For the record, the tears of joy started at “Under the Sea” and occurred many times throughout the film.

I have also cried several times while writing this article, which might be one of the reasons why it took me so long to write; I am now finishing it eight days later (June 3rd). But I had a lot to say, and it all comes from my heart.

I knew that no one was going to ruin this film for me, especially not the racists and naysayers who are afraid of diversity and representation. I went into the theatre with an open heart, and I was ready to accept the new movie as it was.

I got to take that journey all over again, with a new cast in a different time. It was such a magical experience. I’m still singing and crying and feeling all the emotions.

Yes, there were many changes to the story and the songs, which people have been arguing about ad nauseam since before the film was ever released. I appreciate the new film on its own merits, and I think most of the changes work well in the context of this version of the story.

Both films can and should coexist. The new film honors the original and captures the same spirit, but stands on its own… what do you call them?

Oh, feet.

It’s important to remember that this is an adaptation of the story for the modern era. 1989 was a very different world than 2023, and it is completely reasonable to accept that the story has evolved over the years.

The new version represents who Ariel is today, as her journey throughout the decades has taken her to many places.

Since this is a queer analysis of the story, it is also important to recognize that these are scary times we live in now. Oppressive laws are being put into place to take away our rights, and there is so much blatant racism, homophobia, and transphobia all over the place. We are still fighting for our lives.

I believe that Ariel still has a lot to teach the human world about kindness and compassion.

My hope is that she helps those who are lost to rediscover their voice and find the courage to speak up and be themselves during these difficult times.

Just as she sang for me all those years ago, I hope her song and message reach those who need it most.

Happy Pride

from the fabulous, queer little boy who just wanted to be a mermaid.

❤️🏳️🌈🧜🏼♂️

What a beautiful and heartfelt writing about The Little Mermaid and about you personally. It has opened my eyes a lot. So well written and such good points historically, musically, writing, characterization, etc. Thank you so much.

Leslie