Calamus: The Roots of Manly Love

Exploring the Roots

The “Calamus” section in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass is named after the calamus plant (Acorus calamus), also known as “sweet flag,” which grows in wetlands and is similar to a cat-tail.

Many scholars and critics have noted that the floral spadix has a decidedly phallic appearance, but of greater significance to Whitman were the plant’s “pink-tinged roots.”

The “love-root” may also be interpreted as a phallic symbol, but it carries multiple meanings simultaneously. Whitman loved to play with language and celebrated his contradictions and multitudes.

He was also brilliant at marketing himself and curated his public image throughout his career. Despite some of the frankness in his poetry, he was also judiciously vague at times, which has allowed him to continue to be an enigma to this day.

There has been a great deal of praise and controversy regarding the Calamus poems, which is usually centered around the topic of homosexuality.

While it is true that Calamus is mostly about relationships between men, I believe it is crudely reductive to assume that sex is the sole or primary focus.

When Calamus was first published, the word “homosexuality” hadn’t been invented yet.

Whitman used his own language to talk about love and relationships, and I think it is important to try to understand Whitman in his own time and in his own words, and be careful not to distort his vision through our modern filters.

Sexuality certainly plays a role in these poems, but I believe Whitman is more concerned with laying the fertile foundation of love to grow beautiful friendships between men.

He does not focus specifically on the phallic inflorescence, but digs much deeper, down to the roots, to the interconnectedness of mankind.

Calamus is a celebration of masculinity, friendship, compassion, affection, strength, and courage. It is a message of universal love to and for all men.

Adhesive Man-Love

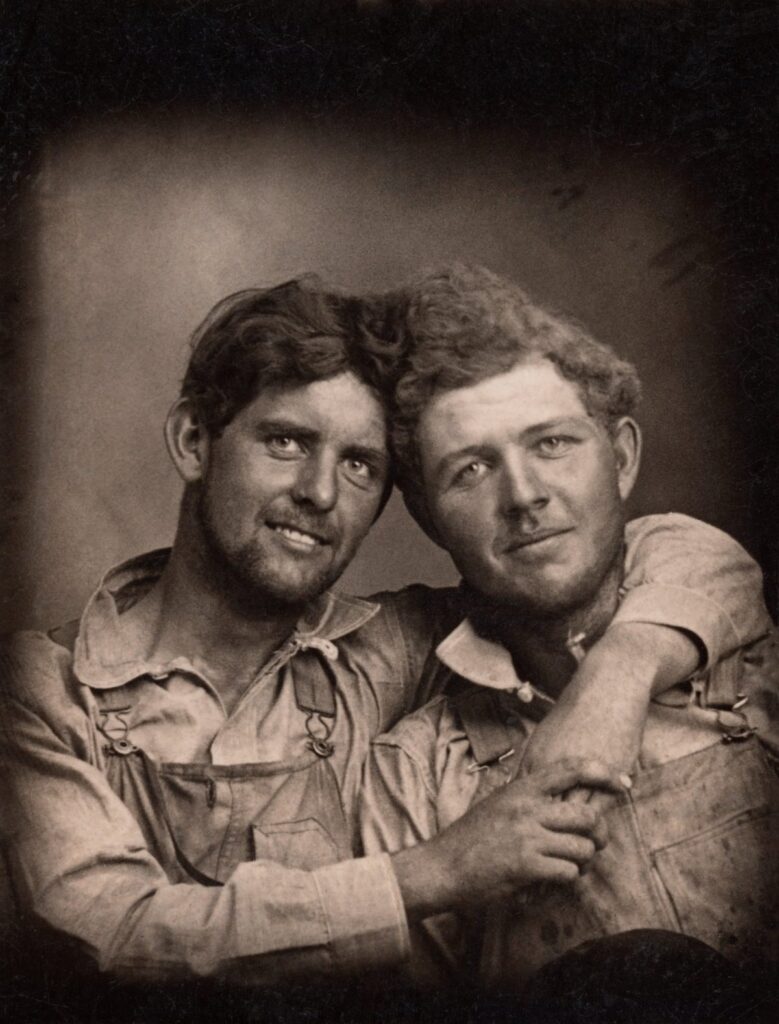

Throughout his work, Whitman described manly love as “adhesiveness,” referring to friendship and camaraderie.

This is compared and contrasted with “amativeness,” referring to romantic and sexual love. Whitman borrowed these terms from phrenology, a popular “pseudoscience” in the 19th century.

Whitman’s concept of adhesiveness or manly love is simultaneously platonic and romantic. He often uses “friend” and “lover” interchangeably.

In the aromantic community, the type of emotional attraction that is somewhere between platonic and romantic is called “alterous.”

This is a very modern term, but I mention it because it demonstrates that human feelings and relationships have always been complex, despite great efforts to pigeonhole people into narrowly defined categories.

Whitman used his own language to describe his own feelings in his own way.

The themes of Whitman’s philosophy of adhesiveness include brotherly love, male bonding, close friendships, mutual admiration and support, and strong emotional connections between men.

The Calamus cluster contains elements of eroticism, but none of the poems are sexually explicit. It is pretty tame compared to other sections of Leaves of Grass, especially its companion piece, “Children of Adam.”

Just as Calamus is about adhesiveness, Children of Adam is about amativeness. The two sections were intended to complement each other. Whitman reserved his smuttier expressions for the “Adam” poems, which caused quite a stir at the time.

Even though Children of Adam explores sex through a heteronormative lens, his admiration and affection for men remains apparent throughout. He did name the cluster of poems after the prototypical man, after all.

I will be taking a closer look at the Adam poems in a separate article, but their relationship with Calamus is important to mention.

“I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing”

Written in the late 1850s, the original twelve poems that would become Calamus were titled “Live Oak, with Moss.” In their original sequence, they tell a very personal story about love and loss in Whitman’s life.

When the Calamus cluster was first published in the third edition of Leaves of Grass in 1860, it was comprised of 45 poems, including the Live Oak poems presented in a different order, which dispersed the original narrative.

Calamus 9, often called “Hours Continuing Long,” shows Whitman at his most vulnerable, pouring out his feelings of loneliness, abandonment, shame, and sorrow. This poem was published only in the 1860 edition of Leaves.

Whitman’s original title and sentiment are preserved in the poem, “I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing.” He is in a more contemplative mood as he ponders the phallic symbolism of the oak tree and fashions a talisman out of a twig wrapped in moss.

I saw in Louisiana a live-oak growing,

All alone stood it and the moss hung down from the branches,

Without any companion it grew there uttering joyous leaves of dark green,

And its look, rude, unbending, lusty, made me think of myself,

But I wonder’d how it could utter joyous leaves standing alone there without its friend near, for I knew I could not,

And I broke off a twig with a certain number of leaves upon it, and twined around it a little moss,

And brought it away, and I have placed it in sight in my room,

It is not needed to remind me as of my own dear friends,

(For I believe lately I think of little else than of them,)

Yet it remains to me a curious token, it makes me think of manly love;

For all that, and though the live-oak glistens there in Louisiana solitary in a wide flat space,

Uttering joyous leaves all its life without a friend a lover near,

I know very well I could not.

“We Two Boys Together Clinging”

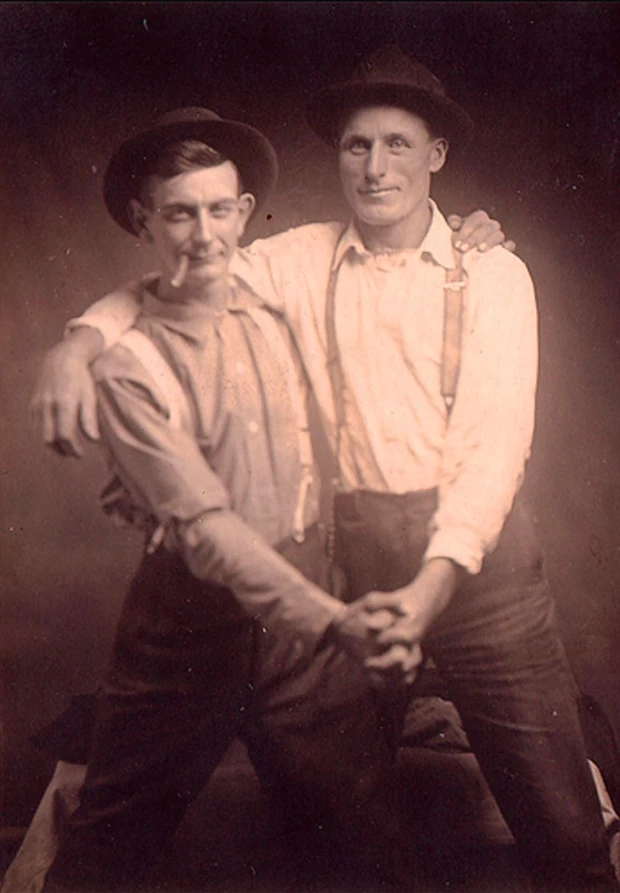

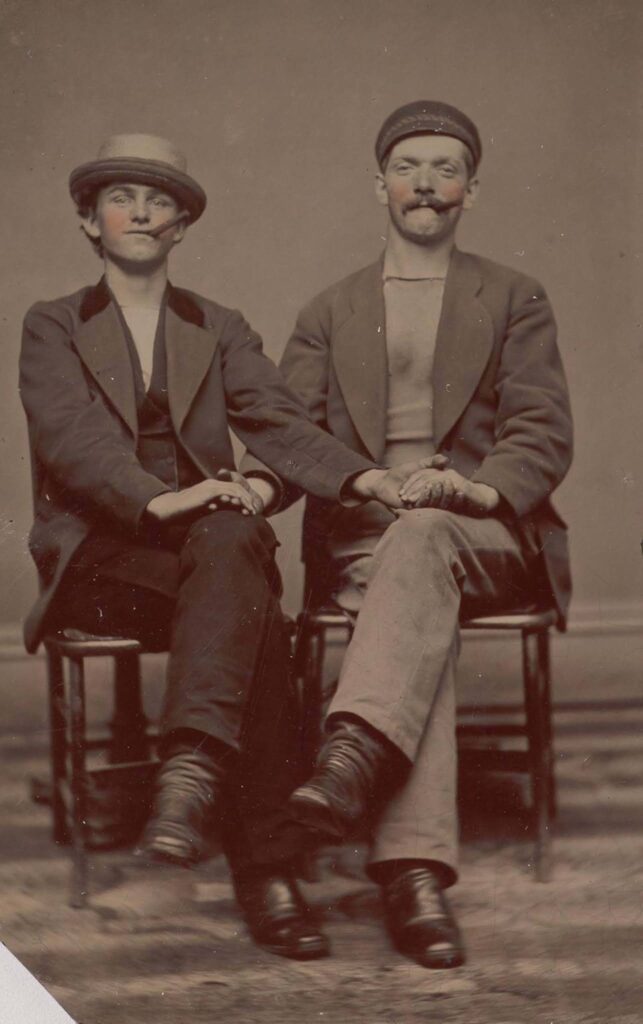

One important Calamus poem with homoerotic subtext is “We Two Boys Together Clinging.” The physicality and power play are often interpreted as erotic, but the relationship of the two boys is deliberately ambiguous.

The poem also expresses a fearless rebellion against authority, with all of its alarming of priests and mocking of statutes.

It can be interpreted as a romantic or sexual relationship between two men, the adventures of two friends who travel together, two soldiers marching in unison, two outlaws on the run, or two children engaging in rambunctious horseplay.

The two boys find strength in their “clinging,” which is synonymous with adhesiveness and bonding.

It could describe all kinds of interpersonal connections, including deep emotional and social bonds, intimate conversations, affectionate embraces, holding of hands, sensual touch, wrestling and feats of physical and athletic prowess, as well as sexual activities.

Similar sentiments are found all throughout Leaves of Grass. For example, in the last section of “Starting From Paumanok,” Whitman uses the word “camerado,” a term he invented as a Latinized form of comrade:

“O camerado close! O you and me at last, and us two only.” Hand in hand, the two camerados travel forth triumphantly as the path ahead opens before them.

A poem from Children of Adam, “We Two, How Long We Were Fool’d,” could very well depict the same two, now older and wiser after many adventures together: “We have circled and circled till we have arrived home again.”

We two boys together clinging,

One the other never leaving,

Up and down the roads going, North and South excursions making,

Power enjoying, elbows stretching, fingers clutching,

Arm’d and fearless, eating, drinking, sleeping, loving,

No law less than ourselves owning, sailing, soldiering, thieving, threatening,

Misers, menials, priests alarming, air breathing, water drinking, on the turf or the sea-beach dancing,

Cities wrenching, ease scorning, statutes mocking, feebleness chasing,

Fulfilling our foray.

“City of Orgies”

Another poem with erotic implications that gets a lot of attention due to the title alone is “City of Orgies.”

The poem is an ode to Manhattan and the spectacle of its population. Whitman loved to watch people on his excursions and frequently recorded his observations in his writing.

To Whitman, the people were the most important part of the city. He saw potential friends and lovers everywhere he went, which filled his heart with joy and ignited his imagination.

He also expresses this in another Calamus poem, “To a Stranger”: “Passing stranger! you do not know how longingly I look upon you…”

In “Give Me the Splendid Silent Sun,” (a poem from the “Drum-Taps” section) Whitman sings about the “interminable eyes” of the Manhattan crowds.

He demands to be given “comrades and lovers by the thousand! Let me see new ones every day—let me hold new ones by the hand every day!”

It is possible that Whitman could be referring to literal orgies. In the 1860 version of “A Song of Joys,” (then titled “Poem of Joys”) he expresses that all the flitting faces on the street are welcome to him.

He also enthusiastically exclaims, “O I cruise my old cruise again!” which, to some, may conjure up images of Whitman cruising for sex “in paths untrodden,” or in secret places where men meet up to have sex.

There may be some truth to this, but I take these interpretations with a generous grain of salt.

The word “orgies” is also featured in an Adam poem, “Native Moments,” where it is used in a much more Bacchanalian sense.

Whitman’s description of his “libidinous joys” and “loose delights” adds both an elaboration and a counterpoint to his sentiments in City of Orgies.

City of orgies, walks and joys,

City whom that I have lived and sung in your midst will one day make you illustrious,

Not the pageants of you, not your shifting tableaus, your spectacles, repay me,

Not the interminable rows of your houses, nor the ships at the wharves,

Nor the processions in the streets, nor the bright windows with goods in them,

Nor to converse with learn’d persons, or bear my share in the soiree or feast;

Not those, but as I pass O Manhattan, your frequent and swift flash of eyes offering me love,

Offering response to my own—these repay me,

Lovers, continual lovers, only repay me.

“What Think You I Take My Pen in Hand?”

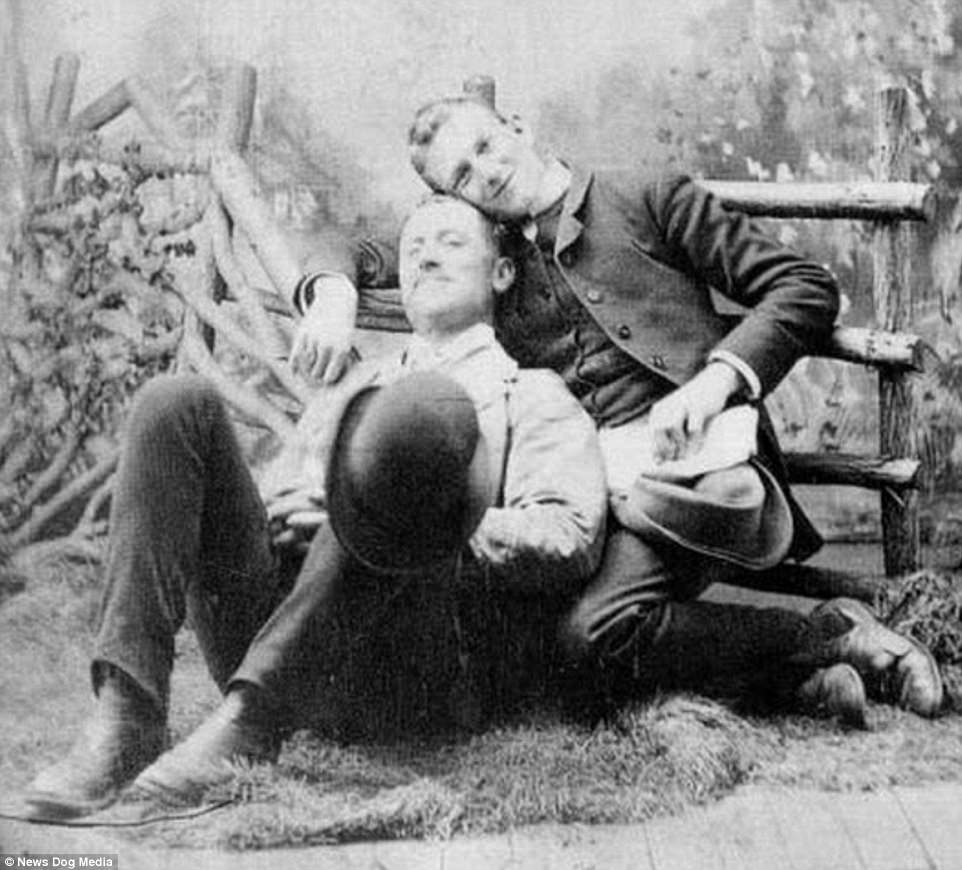

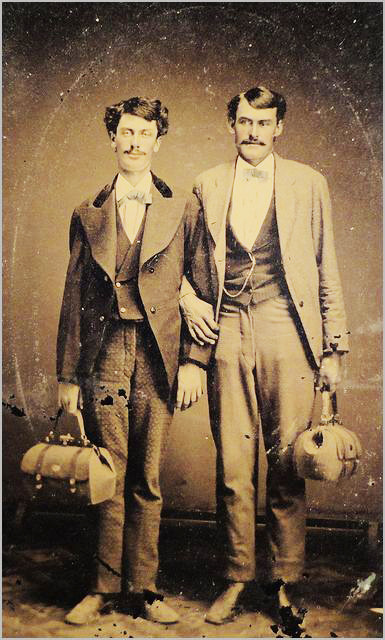

Throughout Calamus, portrayals of physical affection between men are usually non-sexual.

The truth is that Whitman really loved a good hug.

One poem that exemplifies this is “What Think You I Take My Pen in Hand?”

Whitman tells his readers that what inspired him to pick up his pen and write this poem was not some marvelous spectacle he witnessed throughout the city, but the sheer simplicity of two friends embracing and kissing each other on the pier.

It is a prime example of Whitman’s people-watching poems.

What think you I take my pen in hand to record?

The battle-ship, perfect-model’d, majestic, that I saw pass the offing to-day under full sail?

The splendors of the past day? or the splendor of the night that envelops me?

Or the vaunted glory and growth of the great city spread around me?—no;

But merely of two simple men I saw to-day on the pier in the midst of the crowd, parting the parting of dear friends,

The one to remain hung on the other’s neck and passionately kiss’d him,

While the one to depart tightly prest the one to remain in his arms.

“A Glimpse”

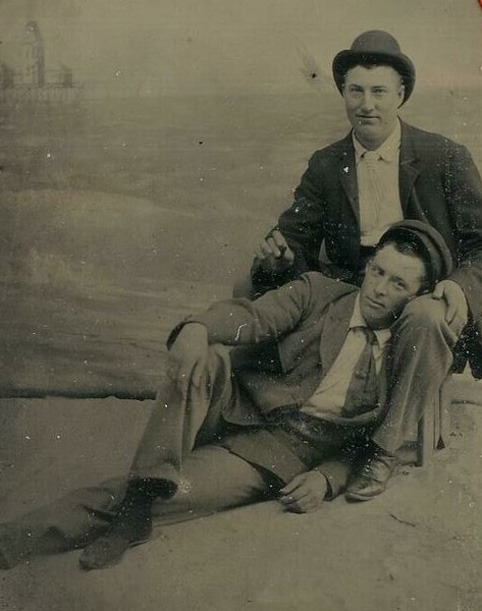

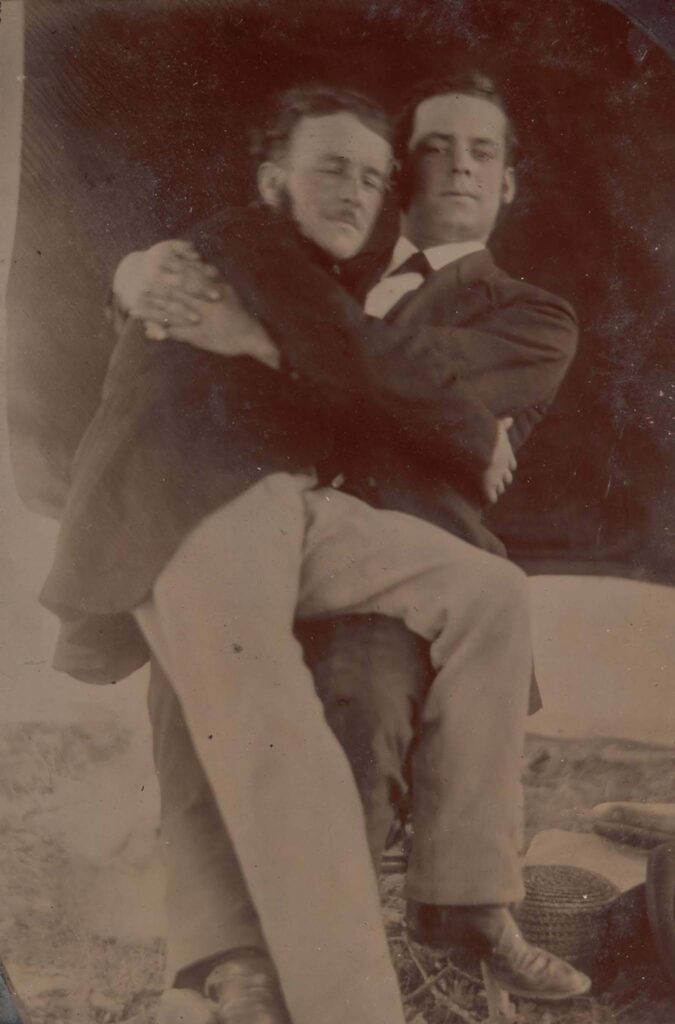

Another example is “A Glimpse,” which provides a candid snapshot of a bar-room full of working class men drinking and making bawdy jokes.

Whitman sits inconspicuously in a corner by himself, until a young man joins him, and they sit together, holding hands, silently and contently.

In another Calamus poem, “Of the Terrible Doubt of Appearances,” Whitman states that many things in life are uncertain and speculative, and his senses may deceive him at times.

But when his friend or lover is holding his hand, everything becomes clear and he is “charged with untold and untellable wisdom,” requiring “nothing further…”

Even though “A Glimpse” describes a bar of blue collar workers, the poem may actually be about Pfaff’s, a beer cellar on Broadway that served as a major social hub for New York’s Bohemian art scene in the late 1850s.

Whitman hobnobbed with famous writers, actors, and musicians, and was introduced to the “underground gay scene” of the time.

These experiences may have influenced his Live Oak poems, and ultimately contributed to the success of the third edition of Leaves of Grass in 1860.

A glimpse through an interstice caught,

Of a crowd of workmen and drivers in a bar-room around the stove late of a winter night, and I unremark’d seated in a corner,

Of a youth who loves me and whom I love, silently approaching and seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand,

A long while amid the noises of coming and going, of drinking and oath and smutty jest,

There we two, content, happy in being together, speaking little,

perhaps not a word.

“For You O Democracy”

Whitman insisted that his intentions for Calamus were always political, and as the years wore on, he further emphasized his patriotic proclamations.

In “For You O Democracy,” he declares that he will “plant companionship thick as trees” all over America, and that the “manly love of comrades” will bring peace and unity to his proud nation.

It was originally published as Calamus 5 in 1860, and was later split into two poems.

The second poem is found in the “Drum-Taps” section, titled “Over the Carnage Rose Prophetic a Voice,” in which the eponymous voice sings:

“Be not dishearten’d, affection shall solve the problems of freedom yet,

Those who love each other shall become invincible…”

He also expresses this vision in another Calamus poem, “I Dream’d in a Dream,” where he shares his dream of a peaceful utopian city founded on and fortified by the “robust love” of male friendship.

Whitman was deeply affected by the American Civil War. His younger brother, George, enlisted in the spring of 1861. In December of the following year, Walt saw his brother’s name in a list of soldiers wounded in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

He traveled to Washington, D.C. and was relieved to discover his brother’s injuries were not serious. George would continue to serve throughout the remainder of the war.

But upon witnessing the gruesome horrors of the war, Walt Whitman became determined to do everything in his power to bring comfort and healing to those afflicted.

He visited thousands of soldiers in the hospitals, sitting at their bedside, holding their hands, and listening to their stories.

No matter which side of the war they were on, they were all equal in Whitman’s heart.

He carried a haversack containing food, drink, newspapers, articles of clothing, small sums of money, and other gifts. He helped many men write letters to their families.

Whatever they needed, he strived to accommodate them.

He dressed their wounds and saved several limbs from unnecessary amputation. Sadly, there were also many men who did not survive their injuries, and he wrote to their families to break the news.

The deep love and compassion he had for these men cannot be denied.

His experiences and feelings are famously documented in the “Drum-Taps” poems, and further reflections are found in “Memoranda During the War.”

During his time in D.C., Whitman often saw Abraham Lincoln passing by on the street.

Lincoln was Whitman’s personal hero. He agreed with the President’s stance that the war was a bloody mess, but it was necessary to abolish slavery in America.

When Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, Whitman was heartbroken. He wrote four poems for his beloved President, including “O Captain! My Captain!” and “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” He also gave lectures on Lincoln between 1879 and 1890.

In Democratic Vistas, Whitman called out the heartlessness, corruption, and greed of the post-war Gilded Age. The nation lost sight of the values and lessons learned during the war, and turned instead to money and materialism.

Whitman didn’t want people to forget the sacrifices of his Captain and the brave soldiers who gave their lives for his country.

He declared that true Democracy is not only about the Individualism, but that the other half is “Adhesiveness or Love, that fuses, ties and aggregates, making the races comrades, and fraternizing all.”

Come, I will make the continent indissoluble,

I will make the most splendid race the sun ever shone upon,

I will make divine magnetic lands,

With the love of comrades,

With the life-long love of comrades.

I will plant companionship thick as trees along all the rivers of America, and along the shores of the great lakes, and all over the prairies,

I will make inseparable cities with their arms about each other’s necks,

By the love of comrades,

By the manly love of comrades.

For you these from me, O Democracy, to serve you ma femme!

For you, for you I am trilling these songs.

“This Moment Yearning and Thoughtful”

Whitman’s vision extended to the entire world. He believed that his philosophy of adhesive man-love could transcend barriers of culture and language.

In “This Moment Yearning and Thoughtful,” he daydreams about men in other countries and wonders what it would be like to bond with them in brotherly love.

Imagine if more men could look beyond identities, labels, and the differences that divide us, and simply love each other without fear or shame.

I believe there would be less insecurity and violence and greater global harmony.

This moment yearning and thoughtful sitting alone,

It seems to me there are other men in other lands yearning and thoughtful,

It seems to me I can look over and behold them in Germany, Italy, France, Spain,

Or far, far away, in China, or in Russia or Japan, talking other dialects,

And it seems to me if I could know those men I should become attached to them as I do to men in my own lands,

O I know we should be brethren and lovers,

I know I should be happy with them.

Peter Doyle

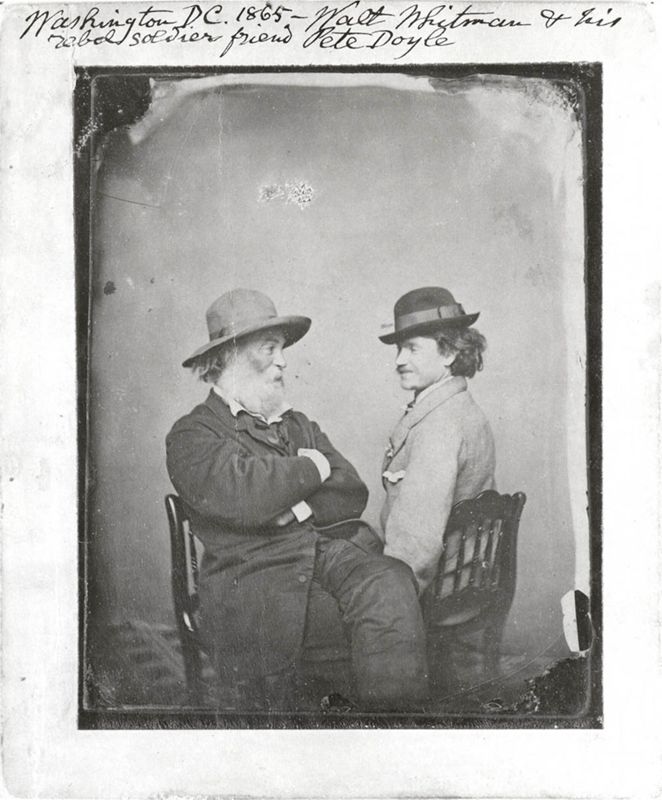

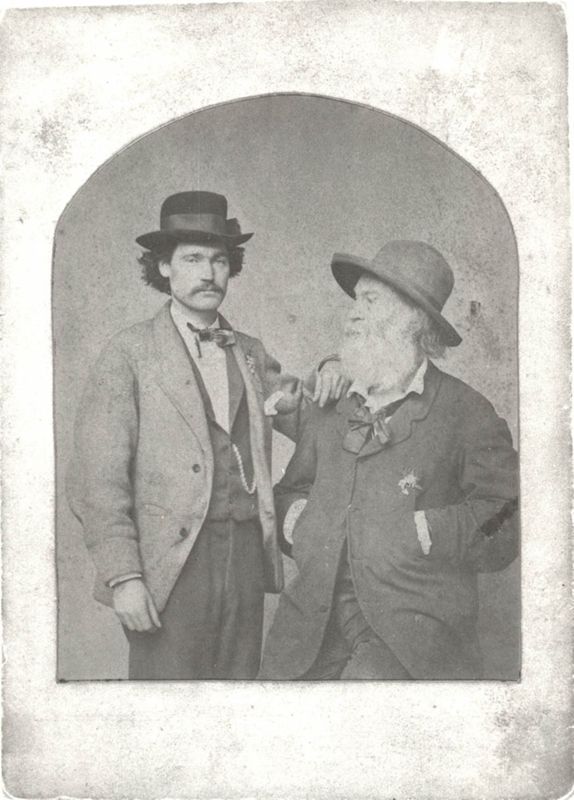

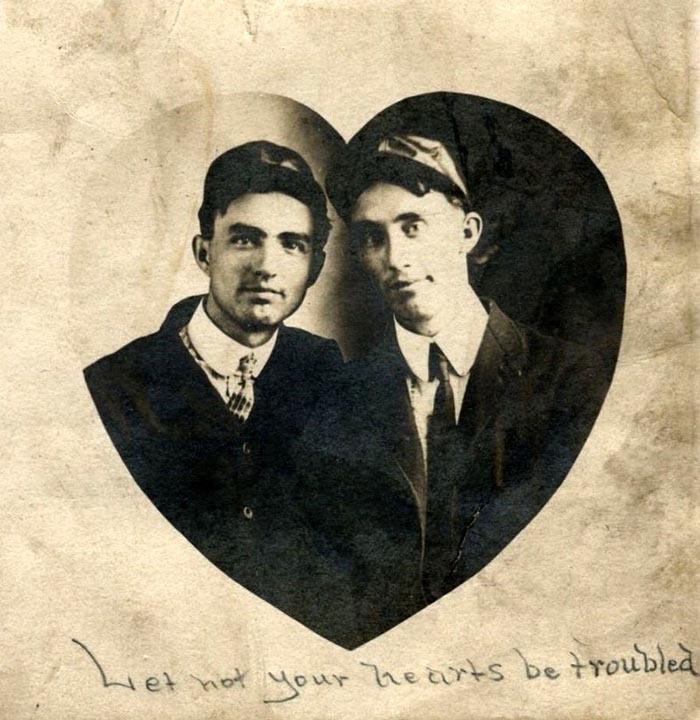

Whitman had several intimate friends and companions, but his greatest relationship was with Peter Doyle.

They met on a stormy night in 1865 while Doyle was working as a streetcar conductor in D.C. Whitman was his only passenger, and Doyle felt compelled to talk to him. He placed his hand on Whitman’s knee and they immediately understood each other.

Their relationship was very much the epitome of the old adage, “opposites attract.” Whitman was in his 40s and Doyle in his 20s. Whitman had his signature long, grey beard and hair, and Doyle had messy curls and a neat mustache.

Whitman was born in New York and identified with the Union. Doyle was Irish-born, raised in Virginia, and an ex-Confederate soldier. He fought on opposite sides of the battlefield with George Whitman, although Doyle was discharged in 1862.

Walt and Pete were deeply in love. Although the Calamus poems were written several years earlier, Doyle was Whitman’s Calamus lover.

Doyle was the perfect foil for Whitman’s intellectualism. He embodied the handsome, rugged, working class man that Whitman was attracted to.

Whitman did have a particular fondness for the carriage drivers (see my previous comments on Walt the Cruiser).

I also previously mentioned the role of adhesiveness in the Drum-Taps poems. Doyle’s love and presence was no doubt influential on Whitman’s poetry at the time. Whitman even prepared a special manuscript of Drum-Taps just for him.

Doyle also witnessed President Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theatre. When Whitman did his Lincoln lectures several years later, he drew some inspiration from Doyle’s descriptions.

Walt and Pete remained nearly inseparable until Whitman had his first stroke in 1873. He moved to Camden, New Jersey, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

The two continued to be friends, but they drifted apart as Whitman got older.

In his later years, Whitman became a bit of a celebrity to a new generation of men who loved men—individuals identifying as homosexuals, inverts, Uranians… and Calamites.

“Whoever You Are Holding Me Now in Hand”

For over three decades, men all over the world wrote to Whitman to express their admiration and affection, and many also befriended him in person.

In America, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were early supporters, linking Whitman to the Transcendentalism movement in New England. He was also friends with John Burroughs, the naturalist and conservationist.

Another close friend was author William Douglas O’Connor, who wrote The Good Gray Poet in defense of Whitman—an epithet that remains with him to this day.

Later in life, he amassed a significant following of European fanboys, including Edward Carpenter, Bram Stoker, and Oscar Wilde. Whitman was always appreciative, generous, and congenial in his interactions with these men.

In 1890, English physician and sexologist, Havelock Ellis, published his book, The New Spirit, which included an extensive essay on Walt Whitman. It garnered a lot of attention, and numerous people wrote to Whitman about it that year.

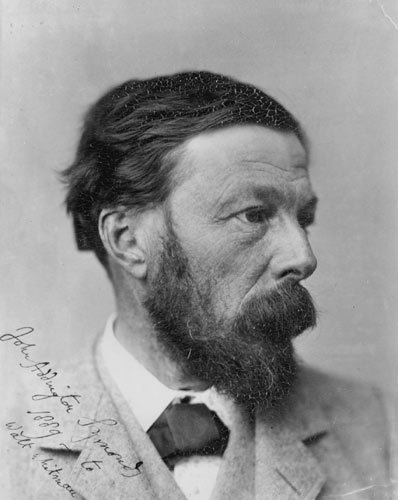

One of those people was John Addington Symonds, an English historian and literary critic known for his writings on Ancient Greece and the Italian Renaissance.

In his letter, Symonds referred to Whitman as “my dear Master.” Such adulation was not uncommon, but on this particular day in August of 1890, Symonds asked Whitman directly if Calamus was about sexual relationships between men.

In his response, Whitman didn’t pull any punches. He stated plainly that the “possibility of morbid inferences” seemed “damnable.” He also told probably the greatest lie of his life: he claimed to have fathered six children out of wedlock.

Symonds began correspondence with Whitman in 1871, and for nearly 20 years the Englishman inquired about these poems. He was obsessed with cracking the Calamus code, and he looked to his “Master” to validate his sexuality.

He was so deeply entrenched in this mission that another English writer, Algernon Charles Swinburne, pejoratively referred to Symonds and other Whitman devotees as “Calamites.”

Whitman respected Symonds and thought his work was valuable, although he found some of the Englishman’s essays to be quite derivative. Symonds made numerous references to the American poet and looked to him as a savior.

But did he truly understand the roots of Calamus and grasp Whitman’s intent? As Whitman told Horace Traubel—his close friend, biographer, and literary executor—that same year: “I don’t think he does.”

In 1890, Walt Whitman was 71 years old. He had suffered several strokes. Despite his resilience, his health was declining. He knew he was in the final years of his life.

He had given so much of himself for so long. In his old age, there were times when he didn’t want to be bothered, and he didn’t owe anyone an explanation. He grew weary of Symonds’s incessant probing and derailed the Englishman’s efforts with a tall tale.

Whitman predicted that something like this could happen. He knew that ambitious seekers like Symonds would try to read between the lines to uncover some hidden truth, or, more accurately, to justify their assumptions.

In “Whoever You Are Holding Me Now in Hand,” Whitman warns the reader: before you read any further, “I am not what you supposed, but far different.”

If you proceed, you must give up everything you know… or think you know.

“But these leaves conning you con at peril…” These pages will deceive you if you’re not ready to receive their meaning. Their true nature will elude you continuously. Just when you think you’ve figured him out… Whitman evades you again.

Imagine how that must have driven Symonds crazy.

Whitman challenges the reader: “Who is he that would become my follower? Who would sign himself a candidate for my affections?” He doesn’t think you have what it takes, and that you should just turn around and give up.

He isn’t looking for admiration and empty praise from adoring fans who think they know him.

As much good as his poems can contribute to the world, “they will do just as much evil, perhaps more,” if misconstrued.

His meaning won’t come to you in a house, or amongst the company of others. His words will appear as nonsense if you try to read them in a library.

To truly get to the heart of Whitman’s poetry, you must go alone, deep in the woods, high on a hill, or out to sea.

It is not enough to read the words, your heart must be open and attuned to this Love.

If you are worthy, Whitman gives you permission to kiss him, and these are some of the most compelling lines in the poem:

“With the comrade’s long-dwelling kiss or the new husband’s kiss,

For I am the new husband and I am the comrade.”

He also invites you to thrust him beneath your clothing so he can feel your heartbeat, or rest at your side while you travel, for he is happy to simply be touching you in some way.

In these lines, he is referring to the book, but he is also saying that he is the book, and the words on the pages are as if he is speaking directly to you.

Whitman passionately describes these physical affections, enticing the reader, but then he turns to cast his doubt once more.

He states that it is useless to keep guessing “that which I hinted at”—perhaps the mysterious Holy Grail of Calamus that Symonds sought for so many years.

Finally, he urges the reader or would-be disciple to “release me and depart on your way.” I believe that Whitman’s story about having six children was his way of telling Symonds to release him and cease this pursuit.

Whitman issues a similar warning in another Calamus poem, “Are You the New Person Drawn Toward Me?”

The person who is attracted to him may have this ideal image of him, and Whitman cautions that he isn’t who you think he is. He questions if his admirer has considered “that it may be all maya, illusion?”

Whoever you are holding me now in hand,

Without one thing all will be useless,

I give you fair warning before you attempt me further,

I am not what you supposed, but far different.

Who is he that would become my follower?

Who would sign himself a candidate for my affections?

The way is suspicious, the result uncertain, perhaps destructive,

You would have to give up all else, I alone would expect to be your sole and exclusive standard,

Your novitiate would even then be long and exhausting,

The whole past theory of your life and all conformity to the lives around you would have to be abandon’d,

Therefore release me now before troubling yourself any further, let go your hand from my shoulders,

Put me down and depart on your way.

Or else by stealth in some wood for trial,

Or back of a rock in the open air,

(For in any roof’d room of a house I emerge not, nor in company,

And in libraries I lie as one dumb, a gawk, or unborn, or dead,)

But just possibly with you on a high hill, first watching lest any person for miles around approach unawares,

Or possibly with you sailing at sea, or on the beach of the sea or some quiet island,

Here to put your lips upon mine I permit you,

With the comrade’s long-dwelling kiss or the new husband’s kiss,

For I am the new husband and I am the comrade.

Or if you will, thrusting me beneath your clothing,

Where I may feel the throbs of your heart or rest upon your hip,

Carry me when you go forth over land or sea;

For thus merely touching you is enough, is best,

And thus touching you would I silently sleep and be carried eternally.

But these leaves conning you con at peril,

For these leaves and me you will not understand,

They will elude you at first and still more afterward, I will certainly elude you,

Even while you should think you had unquestionably caught me, behold!

Already you see I have escaped from you.

For it is not for what I have put into it that I have written this book,

Nor is it by reading it you will acquire it,

Nor do those know me best who admire me and vauntingly praise me,

Nor will the candidates for my love (unless at most a very few) prove victorious,

Nor will my poems do good only, they will do just as much evil, perhaps more,

For all is useless without that which you may guess at many times and not hit, that which I hinted at;

Therefore release me and depart on your way.

The Roots are in the Heart

According to the Dionysiaca by Nonnus in the 5th century, Calamos was the son of the river god, Maiandros. One day, he and his mortal lover, a young man named Carpos, decided to have a swimming race.

Calamos reached the other side easily, but Carpos drowned under a giant wave. In his grief, Calamos decided that he too should drown and join his beloved. Because of his self-sacrifice, the gods transformed him into a water reed.

The ancient Greek word Κάλαμος also means “reed pen,” and is etymologically related to the Sanskrit कलम kalama and Arabic قلم qalam, which carry the same meaning.

The pen was Whitman’s tool of communication. Symbolically, it was also his pointer-stick in his role as teacher, his sceptre in his role as sensual mystic, and a representation of his phallus.

His words are his orgasmic manifestation on paper—his inflorescence in full bloom. However, the roots of Calamus are not in the loins, but in the heart.

Love, unity, and harmony are the foundational tenets upon which grows Whitman’s Calamus philosophy, along with sensuality and the basic need for human touch, as well as deep emotional intimacy and social bonds.

The 20th century American poet, James Broughton, once said that “the penis is the exposed tip of the heart… the wand of the soul.” So, too, does the phallic flower of Acorus calamus take root in the hearts of men.

Happy 205th Birthday, Master Whitman!

(May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892)

With Love, a Devoted Calamite.

References

Cady, Joseph. “Not Happy in the Capitol: Homosexuality and the ‘Calamus’ Poems.” American Studies. Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 5–22. September 1978. DOI: 10.1353/amsj.v19i2.2263.

Cohen, Matt; Ed Folsom & Kenneth M. Price (general editors). The Walt Whitman Archive. https://whitmanarchive.org/

Ellis, Havelock. The New Spirit. London: George Bell & Sons, 1890.

Erkkila, Betsy. Walt Whitman’s Songs of Male Intimacy and Love: “Live Oak, with Moss” and “Calamus.” Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011.

Folsom, Ed & Kenneth M. Price. Re-Scripting Walt Whitman: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Grosskurth, P. M. “Swinburne and Symonds: An Uneasy Literary Relationship.” The Review of English Studies. Vol. 14, No. 55, pp. 257–268. August 1963. DOI: 10.1093/res/xiv.55.257.

Helms, Alan. “Whitman’s ‘Live Oak with Moss.’” The Continuing Presence of Walt Whitman. pp. 185–205. Robert K. Martin (editor). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1992.

Herrero Brasas, Juan A. Walt Whitman’s Mystical Ethics of Comradeship: Homosexuality and the Marginality of Friendship at the Crossroads of Modernity. Albany: SUNY Press, 2010.

Kaplan, Andrew D. (director). In Search of Walt Whitman. Documentary. East Rock Films, 2020.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

LeMaster, J.R. & Donald D. Kummings (editors). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998.

Mackey, Nathaniel. “Phrenological Whitman.” CONJUNCTIONS. Volume 29, Tributes. Fall 1997. https://www.conjunctions.com/print/article/nathaniel-mackey-c29

Martin, Robert K. (editor). The Continuing Presence of Walt Whitman: The Life after the Life. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1992.

McGee, Tim (instructor). “Talks with Walt.” Learnstrong. Online lectures. https://www.learnstrong.net/talks-with-walt

Murray, Martin G. ‘“Pete the Great”: A Biography of Peter Doyle.’ Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1–51. July 1, 1994. DOI: 10.13008/2153-3695.1429.

O’Connor, William Douglas. The Good Gray Poet: A Vindication. New York: Bunce & Huntington, 1866.

Parker, Hershel. ‘The Real “Live Oak, with Moss”: Straight Talk About Whitman’s “Gay Manifesto.”’ Nineteenth-Century Literature. Vol. 51, No. 2, pp. 145–160. September 1996. DOI: 10.2307/2933958.

Pollak, Vivian R. The Erotic Whitman. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Robertson, Michael. Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Schmidgall, Gary. Walt Whitman: A Gay Life. New York: Plume, 1998.

Shively, Charley. Calamus Lovers: Walt Whitman’s Working-Class Camerados. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1987.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. “Recollections of Professor Jowett.” Studies in Prose and Poetry, p. 34. London: Chatto & Windus, 1894.

Traubel, Horace. With Walt Whitman in Camden, Volume 7: July 7, 1890 – February 10, 1891. Southern Illinois University Press, 1992.

Whitman, Walt. Democratic Vistas. Independently published. Washington, D. C., 1871.

—. Leaves of Grass and Other Writings: Authoritative Texts, Other Poetry and Prose Criticism. Michael Moon, Edward Sculley Bradley & Harold William Blodgett (editors). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002.

—. Leaves of Grass, 1860: The 150th Anniversary Facsimile Edition. Jason Stacy (editor). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2009.

—. Memoranda During the War. Independently published. Camden, NJ. 1875-76. The Walt Whitman Archive. https://whitmanarchive.org/item/ppp.01875

Very well written and so thorough!! A beautiful glimpse into that most beloved selection of Whitman’s poems. Thanks for sharing your insights